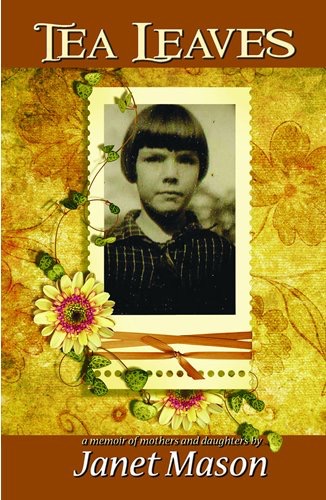

In honor of my book Tea Leaves, a memoir of mothers and daughters being featured on the I Heart Sapph Books website, I am posting the first chapter below for you.

“Your grandmother read tea leaves.”

Startled, I looked up at my mother, sitting in her gold velour chair next to the end table scattered with a few library books. From my mother’s lips, this statement was a bad omen. My atheist, Bible-burning, skeptical-of-anything-less-than-scientific mother had long been a woman who believed in nothing.

Superstition—even applied to a previous generation—was not admissible.

“What did she see?”

“Her own face, probably.” My mother shrugged. “I made fun of her and told her she was old-fashioned and superstitious. Eventually, she stopped talking about it.”

I stopped to ponder this sliver passed to me about my grandmother, my mother’s mother, who died when I was twelve. I was thirty-four years old, and this was the first time my mother told me that my grandmother had read tea leaves.

“Did she read them often?”

“I don’t know. Often enough, I guess. She used to read cards, too—ordinary playing cards. She would take them from the deck and lay them out on the wooden table we had in the kitchen. An ace of hearts good luck, an ace of spades death.”

My mother’s shudder punctuated the end of her sentence.

She was seventy-four, the same age as my grandmother when she died.

My mother’s matter-of-fact tone and my diversion into my grandmother’s tea leaf reading traditions did nothing to alleviate the direness of my visit. It was a Sunday afternoon in early June. Earlier in the day, my partner, Barbara, and I had been clearing out cobwebs in the corners of the ceiling of the house that we had just bought and moved into, when I had the sudden urge to call my mother. My instincts were right. My mother told me in an uncharacteristically faint voice that she had woken up a few days ago with a crushing pain in her sternum.

“I felt like I was having a massive coronary,” she told me.

My mother—who never believed in doctors—went to one immediately. He ordered some X-rays, told her it was arthritis, and sent her home with some extra strength Tylenol. When she told me this, my mind reeled. This was my mother—someone who walked four miles every day.

“Why didn’t you call?” I had asked her on the phone.

“I just did,” she replied.

I didn’t argue, but the fact was that I had called her.

Barbara was listening to me and could tell that something was wrong. “You better go,” she said. “I’ll stay here and take care of things.”

Barbara has always hated change. I often joked that that was the reason we were together for so long. We got together ten years ago when I was twenty-four, the same age my mother was when she met and married my father, and Barbara was thirty-two. Barbara was close to her own mother, who lived in Pittsburgh, six hours away from our home in Philadelphia, and often helped her out financially.

My mother always told me when I was growing up that “You can’t criticize a man for being good to his mother.” When she and my father were first married, he would come home late from work and wouldn’t be hungry for dinner. “I found out,” my mother would say, “that he was stopping at his mother’s house after work and having a piece of cake with her.”

In many little ways Barbara was a lot like my father. Just the other day, she’d left her window down in the car when I had put the air on, stubbornly insisting that she was letting the hot air out. (My father always did the same exact thing.) And shortly after we moved into our first apartment together, she went into her toolbox, took out her ratchet wrench and very sincerely told me what it was and how to use it. I found the way that she was telling me about the ratchet wrench—“You really should know about this”—to be endearing, not patronizing. I waited for her to finish. Then I reminded her of my summers of swing shift at the same industrial plant where my father worked, where I wore a hardhat and learned to drive a ten-speed flatbed truck. But it was Barbara who described herself as a “femmy butch.” I would sometimes jokingly refer to her as my “lesbian husband.” That she was so close to her own mother meant that she understood my concerns about my own parents and in telling me that I should go visit my mother, she was right again.

On the forty-five-minute drive over, through the tree-lined streets of my neighborhood and onto the Pennsylvania turnpike, I was in a panic about the conversation with my mother. There was something in her voice I had never heard before. A dead-end tone. A giving up. Illness or not, I couldn’t conceive of her coming to a standstill. My mind raced.

The bottom of my world began to drop away.

***

“You should have stayed home with Barbara,” she told me after I arrived, “and worked on the house.”

“You know Barbara,” I said, trying to joke. “She probably got on the phone as soon as I left and is over at a friend’s house drumming by now.”

“Barbara is a good drummer and she does know how to enjoy herself,” said my mother, nodding and then wincing from the pain of moving her neck.

“Everything is fine,” she said, noticing my concern. “The extra-strength Tylenol isn’t working yet but it will.”

She shifted in her chair and winced.

“I can make us some lunch,” I said.

“I can do it,” she replied and struggled to stand up.

“Sit down,” I said, as I got up and went to the kitchen where I made a simple meal of miso soup and warmed up brown rice. She joined me at the dining room table.

“The soup is good. You did a good job, Janet.”

“Thank you.”

We ate in silence for several minutes.

“What did the doctor say,” I asked finally.

Her lips pressed into an obstinate straight line.

When I asked again, she told me the HMO primary physician she went to, a man whose office was in a house on the corner of the section where my parents’ lived, refused to give her a referral. The rheumatologist, who my mother wanted to see, was a woman doctor who she saw once before and liked. “I wrote a letter to her,” said my mother, “but I didn’t hear from her.”

“Maybe we can call her,” I replied. “A letter is easy to overlook.”

The stony look on my mother’s face told me that what was going on with her body was her business, and I simply could not drop in on her life and interfere. It had been several months since I had been to visit. Barbara and I had been busy moving from the apartment that we shared for ten years to the house that we were buying, an old farmhouse with a big backyard in the city.

My mother and my father—who was out at his monthly retiree luncheon at a nearby diner—were happy for us. In my parents’ eyes, my decision to purchase a home was the second practical thing I had done as an adult. The first had been to fall in love with Barbara and settle down with her.

Good-natured, likeable Barbara had definitely passed the parent test. That Barbara is a woman—my mother would later refer to her as “my unexpected daughter-in-law”—was superseded by her working- class credentials, a stable government job with the post office and membership in a union. Even my father—who at the time could not wrap his mind around the concept of a women-only dance (where Barbara and I had one of our early dates)—was won over by her genuineness.

When we first got together, my mother hoped that Barbara would be a good influence on me with her stable government job. After finishing college, I took a relatively low-paying job in a nonprofit editorial position and several years later left this stressful situation only to strike out on my own as a freelance writer.

“Why don’t you get a good government job like Barbara?” my mother would ask. “Then you can write on the side.” When I resisted this suggestion, my mother simply shrugged and said, “It looks to me like she wants to be rich and you want to be famous.”

When all was said and done my parents sent me a card with a parachute on it, congratulating me on starting my own business. Before signing the card, my father had had little to say except that it wasn’t a good idea for me to quit my job. His advice didn’t stop me from giving notice and lining up new clients. I understood where my parents were coming from. They had grown up poor and, as adults, made it into the working class. To them, a job was more than a job.

It was survival.

When I’d arrived at my parents’ house and was folding up the paper grocery bags from the health food store and putting them away in the garage, I noticed that the garage was almost sparkling. When I asked my mother who cleaned it, she said, “Your father.” She told me he had been cleaning it nonstop for the past few days—ever since she woke up with the crushing pain in her sternum. This was my father’s way of handling what he could not control. I could see him with his broom and dustpan resolutely sweeping the concrete floor, obsessively dusting and wiping down the cans of paint and his tools with an old rag—as if by the effort of his hard work he could make my mother better.

As my mother and I sat in the living room, the only sound was the ticking of my father’s retirement clock on a high shelf, his reward for thirty-five years of working swing shift at the plant. There was more to my mother’s silence than the privacy she wrapped around herself like a woolen shawl. By not telling me about her problems, she was protecting me. She was the kind of mother who didn’t want her problems to become her daughter’s problems. Through the years, my mother’s auburn hair had faded to reddish beige. Now, as if it had happened overnight, her hair had turned white. She stared at me with her green yellow eyes, cocking her head at me in an owlish curiosity.

I, in turn, searched her face for clues.

Was she reading her own tea leaves?

My mother was forty years old when she gave birth to me. When I was a child, a certain tension hung in the air. “Did you tell her my age?” my mother hissed to me when my best friend made an off-the-cuff remark in front of her about old people. I shook my head with astonishment and growing apprehension.I thought my best friend’s comment was innocent. I hadn’t said anything to her about my parents’ age. But she might have been repeating something that her mother said. My parents were close to twenty years older than the parents of all of my childhood friends. They were always the oldest parents at school functions.

Two disparate generations collided in me. Even as my parents’ stories about WWII—my mother dancing in the streets on V-Day and my father picking coconuts in New Guinea—swirled around me, the Vietnam War raged on the television set. Born in 1959, I was a product of the sixties. In elementary school I wore a peace sign around my neck and refused to salute the flag. This incensed my father, almost to the point of yanking me out of my seat at a Flag Day celebration when I refused to stand up. But my mother held out her hand and said, “Let her do what she wants.”

In my twenties, having older parents meant that I began to worry about their well-being. Even when I didn’t say anything, my mother would read my thoughts. “It’s hard watching your parents get old,” she once told me gently.

When we went for a walk at the shopping mall, she’d comment on the older couples she saw. “One’s in worse shape than the other,” she said, “and they’re holding each other up. What happens when one of them falls over?”

There was no answer to her question. How could I reassure my mother about a future of which I also lived in mortal fear?

My mother had always been active—walking, eating healthy foods, reading widely, taking an interest in life. But over the past several years there were signs that she was withdrawing—what the medical professionals call “shutting down” which can happen before the final stage of life. The first to go were her women’s liberation marches. There weren’t as many of them as in the early seventies when I was a pre-teen and my mother took me with her and, later, in the early 1980s, when I encouraged my mother to come with me. But when smaller demonstrations did turn up, here and there, my mother refused to go.

“Oh, Janet,” she would say, “you know I hate crowds.” The flat, almost sullen tone that crept into my mother’s voice told me that she couldn’t possibly even stand the thought of marching around with a placard, gleefully chanting hey, ho, patriarchy’s gotta go.

Then one year she decided not to plant her garden.

“It’s too much work,” she said, that same tone of resignation pressing down her voice.

For as long as I could remember, after every meal we sorted the garbage from the trash, the mulch-able from the non mulch-able, to make topsoil for next year’s organic garden from the steaming pile of compost in the backyard. My parents liked to joke that they were going to be buried in the compost pile when the time came. Each summer and fall we ate the greens, the tomatoes, the endless dishes of orange squash. The garden was my mother’s all consuming passion, providing her with the company of other gardeners in the organic gardening club.

Several times my mother canceled her plans at the last minute to come and see me. All she said was that she decided she didn’t feel like coming—and then hung up. The thought of her not being able to endure anymore—of her simply laying down and not getting up—was inconceivable.

“After I croak,” my mother once said to me, “you may want to have a baby. Your old high chair is in the attic. It’s in good condition.” When I protested, both to the fact that she would die and that I would someday want to have a baby, she simply shrugged. “Sometimes it’s easier to raise a child without the grandparents around interfering,” she said. “I’m not telling you to have a baby. You have to make up your own mind about things like that. But if you do have one, there’s no reason to go out and buy a new high chair.”

As it turned out, I did need the high chair for a lesbian friend who had adopted a baby. When Barbara and I first got together we had discussed the possibility of adopting a daughter. It was the early 1980s, a few years before lesbians were starting to take trips to the sperm banks. Most of the lesbians we knew with children had them in previous marriages—to men—and more than a few women we knew had been through painful custody battles. Barbara had been briefly married to a man before we met, but had no children. On one of our early dates, Barbara looked at me with her deep-set blue eyes and told me that she’d like to settle down and adopt a child.

Sitting across the table from her in the now long gone Mid-Town Diner in Center City Philadelphia, I remember being so nervous over such an idea that I wanted to run for the door.

We moved in together six months later, and our life together was so full that we put the idea of adopting a child on hold indefinitely. It had been years since Barbara and I had thought about adopting a child and viewing the empty seat of my old high chair that once held my round baby bottom was not going to change it. Still, the empty high chair brought back an old feeling that it would be nice to have a daughter. When my mother referred to the inevitable—“When I croak”—she was telling me, in no uncertain terms, that her life would end one day and mine would go on. My inability to comprehend this, and the immense sadness that I felt underneath, was more than knowing I would miss her: picking up the phone to call her with my latest success or crisis; taking pride in cooking her a special dinner that she praised; or discussing some new insight about the latest novel we both read.

***

This was all true, of course. I would miss her. Terribly.

My mother’s death was unimaginable because she was more than my mother. She was the earth that I sprang from. She was my genesis. My creation story. Like everyone else who had not yet lost a parent, I had no idea what was in store for me as I looked at her sitting in her gold velour chair, her face drawn in on at once contemplative and indifferent. Occasionally, she was still likened to Katherine Hepburn: the inquisitive eyes, high cheekbones, candid manner. But, with age, she looked less like a glamorous young woman and more like the tomboy that she had been as a child, in the pictures I stared into growing up: bowl-cut hair, watchful eyes, stubborn chin. Her features in the photo reflected my own, yet I studied them like the pieces of a puzzle.

Increasingly, as my mother aged, I heard the wavering strains of my grandmother’s voice in hers. As we talked, I recognized that under our conversation was another conversation and under that, yet another. The cadences went back at least three generations. My understanding of my mother and myself had begun with my grandmother. It had taken the better part of a century for their lives to fuse into mine—often in the form of pent-up rage gusting through me.

My grandmother died when I was twelve. She was a spinner in the textile mills of Philadelphia, in the Kensington section where the old warehouses were now old hulls, broken down, abandoned. My mother grew up in this neighborhood of bustling industry—lace factories, Brussels rugs, textile mills, the Stetson hat factory, slaughterhouses full of bloody entrails and squealing animals. Devastating scenes of poverty replaced it—abandoned and crumbling houses, a tent city, homelessness, a child prostitution strip that was one of the largest in the nation. When my mother spoke of this place of her childhood, tears came to her eyes.

My grandmother, Ethel, a devout Episcopalian, life-long Republican, and wearer of white gloves, gave birth to my mother, Jane (Plain Jane, her childhood nickname), who became an equally devout atheist (burning her Bibles in the backyard) and a Democrat. My mother identified with the “silent majority,” but was a feminist ahead of her time, and when the women’s liberation movement caught up with her, she joined it. When I was old enough, she sometimes took me with her, the two of us marching and attending rallies, waving our matching mother/daughter coat hangers at pro-choice events. I was the less adventurous one—hanging back and watching with something bordering on amazement as my mother heckled the hecklers and squeezed the balloon testicles of a Ronald Reagan cardboard cutout.

My mother tossed away conventions with every year that she aged. Heels were replaced with comfortable walking shoes; skirts were exchanged for trousers. Eventually she discarded her bras for the skinny-strapped men’s undershirts that she wore under her cotton blouses and short-sleeved shirts that looked tailored on her slender frame. When referring to her mother’s insistence that she be more of a lady, my mother always said, “Who the hell did she want me to be? Jackie Onassis?”

My mother married my father when she was twenty-five years old—the story was that they met on a blind date outside the “Nut House”—and then they lived in the city for nearly another twenty years. Then, when my mother was forty-four and I was four, we moved to Levittown, a suburban tract house community built in the 1950s, one part industrial village, the other part American Dream. With a hundred-dollar down payment, the houses were affordable enough, and my father worked nearby at the chemical plant, one of the two major employers in the area along with the steel mill.

We lived on Quiet Road in Quincy Hollow (the street names in Levittown all began with the first letter of the section name) where my mother took her daily four-mile walk. “Every day I go around and around these streets like a hamster on a treadmill,” my mother would say. As an adolescent, I fanned my mother’s frustrations into the flames of my own self-destruction. I was drinking and drugging at fourteen. Driving at sixteen. The streets looped around my neck like a noose tightening. For me, drinking and drugging was a form of running away. When I was five I had stored pilfered Cheerios (food for the road) in the bottom drawer of my bureau until a parade of ants sabotaged my plans.

During the blurred years of my adolescence, when I was still in high school, I took the Greyhound bus to New York City. I was seventeen. It was 1976. I had not yet come out. But as if my dormant lesbianism were a homing device, I found a subway train that took me straight to Greenwich Village. When I was back above ground, I found a newspaper stand and bought a Village Voice so that I could read the apartment listings. I was looking for Bleecker Street which I had read about in novels and heard about in songs, but found myself on Christopher Street, hungry, and looking for a place to sit. I spotted a restaurant with tall glass windows that jutted out onto the sidewalk. It looked like a large greenhouse with clear windows. It was early in the afternoon on a Saturday. Through the windows I could see patrons sitting across from each other at small tables. Plants hung down from the ceiling between the tables. The maitre d’ took one look at me and firmly told me that he could only seat two people together. I looked over his shoulder into the room full of, it suddenly dawned on me, men, it was all men, gay men, enjoying their Saturday brunch. I mumbled something and headed back out onto the street. Around the corner I found a restaurant where I sat down at a table by myself, ordered something to eat and opened the pages of the Voice. The apartments were all more expensive than I thought they would be and at the age of seventeen—other than mowing lawns or working the register at a fast-food joint—I had no marketable skills. So I used my return ticket back.

I was always intending to be on my way to somewhere else. But the drinking and drugging just dug me in deeper. Eventually my mother gave me a few not-so-gentle shoves and I ended up being the first in my family and the only one in my peer group to go to college. I lived at home and attended Temple University, in Philadelphia, an hour’s commute away. After graduation, I moved back to the city my parents had fled from but, as a college graduate in a community of intellectuals and artists, I was worlds removed from my origins.

Despite my need to escape, I kept going back. Along with the practical reason of visiting my aging parents—the landscape where I grew up was embedded in me. There are many things that invade the lives of working-class people—chief among them poverty, or in my case, the constant threat of it. There is resignation and frustration, a foreboding sense that things will never change. Then there is the internalized self-hatred, the futility of it all.

The air I grew up breathing in Levittown was chemical-laden. On clear days the fumes were invisible. Overcast days, the air was a dirty glove clasped around our nostrils. When we drove past the marsh-lined road alongside the plant, where the stench was the worst, my mother and I would hold our noses, and my father would call it “the smell of money.”

It was my father’s union job, and my mother’s skill at managing money, that pulled my parents out of the poverty they had grown up in. Perhaps it was because of this belief in the American Dream, be it reality or myth, that I was visited with a vague shimmering presence that eventually I came to call hope.

Economic security can be a breeding ground for denial. My mother, feisty enough to have become mythic in the minds of my father and me, had always lived in mortal fear of losing my father. Her own father had abandoned her family when she was seven, and this no doubt foreshadowed her fear. But her concerns were practical ones. My father worked swing shift in the plant’s boiler room. Accidents happened. Growing up in the industrial northeast, I watched the plant explosions on the nightly news. Then there were the killers that were slow to strike. More than a few of my father’s co-workers were felled by cancer of all types and early heart attacks. The summer I worked at the plant when I was in college, a man fell over dead in the guardhouse before punching out his timecard for the day—at the time, it all seemed so unfair and futile to me.

A spot of asbestos showed up on my father’s lung X-ray. When my mother got the news, her face paled. My mother had always been the strong one. She was traditional in her role of housewife—revolving her schedule around my father’s shiftwork hours, washing his work clothes for the thirty-five years he worked at the plant—but this didn’t stop her from being the one who called the shots.

We never expected that the hand that fed us would come out of the sky to strike her down.

***

Today, my mother and I sat in her living room. It was cool in the house. My mother’s feet rested on an ottoman covered with a thread-worn tapestry. It was a mosaic of earth-toned flowers: rust red, silvery green, dusty blue. Thin black lines outlined heart-shaped petals against a faded ocher background. As my eyes traveled along the lines, I saw my grandmother standing with the other women in the long straight aisles between machines in the textile mill, on tiptoe as she dropped the spindles on their spikes, crouching to check the weave, the warp, the weft. Close to half a century later my mother had taken the discards her mother was allowed to take home from the mill and carefully stitched them into a square cover for the iron-legged ottoman.

All it took was a nod toward the tapestry, a certain look, or a made that didn’t my mother would recite the stories, the same ones she had always told, sometimes with a new insight, a different twist. I always listened, transfixed, as she spoke.

“How many hours a day did Grandmom work in the textile mill?”

My mother looked at me, slightly confused. “I don’t remember. Eight, I guess. Isn’t that how long the work day is?”

I told her I was reading about the labor movement and in the early 1900s, when my grandmother started working, men and women were still striking for the ten-hour day.

“People are always bad-mouthing unions, but without them, we wouldn’t have gotten the eight-hour day,” said my father, who had come home from his plant luncheon and was settling into his favorite chair in the living room.

My mother looked at him and then back at me. “When I worked for the Navy Department, they told us we were better than people in unions. We were white

My father was silent. He looked at his watch and then at the turned off television. The game would be on in another hour.

I sighed, shoulders sagging in resignation.

Ever since I graduated from college, my mother had told me about her life like I was a stranger, her reminders sounding like admonishments: “Working people don’t have a choice about what they do for a living. They just work.” my mother told me this, part of me wondered who she thought I was. Being the first in my family to go straight through high school, much less to graduate from college, did not change the fact of how I was raised. Even so, I was ashamed that my mother thought she had to remind me of the conditions of her life.

My mother felt diminished by her lack of a college education. As far back as I could remember, she always told me, “It’s what’s inside your head that matters,” followed by, “No one can ever take an education away from you.” In graduating from college, I fulfilled my mother’s ambitions. But at the same time, in achieving what she could not, I betrayed her.

She wanted me to have a better life than hers. But the opportunities in my life had been underscored with my mother’s resentments. To gain a better understanding of my life, I went back to research the labor movement, to read its history, its literature. Now my mother was telling me she was white collar, that she felt herself to be “better” than people in unions.

I took a deep breath. My mother was just trying to lend a dignity to her life. She was brainwashed into thinking of herself as white collar and, therefore, better than people in unions. Divide and conquer is how the powers that be have kept people in their places. But our conversation was not about white collar or blue collar. It was not about work even—or the fact that I went to college and my mother did not. We were pressed up against opposite sides of the glass divide in our mother-daughter relationship.

My mother and I were close. We saw eye to eye on most things that mattered. We read the same books, lending them to each other, sometimes even going to the bookstore together and deciding jointly what we wanted to read. There were moments between us when she seemed more like my friend than my mother.

At the same time, there was almost always an unspoken tension between us. The things that cut through us most deeply were also the things that divided us. There was—at least temporarily—my sexuality. When I came out to my parents in my early twenties, I was telling my mother, in particular, that my life would be vastly different than hers. At the same time, my lesbianism was a natural outgrowth of my mother’s feminism that most definitely shaped my early sense of self.

I have always been most comfortable living in the present. Still, the past is always there, threatening to rise up at any moment, especially when my mother—who tended to listen to too much talk radio—insisted that she wanted us to discuss our feelings.

“We never talk about how we feel about things. I don’t mean about books or politics or things like that. I mean how we feel about the things we say to each other,” she once said to me. My mother who had sat on her anger all of her life, except for outbursts of breaking dishes and screaming, suddenly wanted me to discuss my feelings. She wouldn’t drop the subject and I found myself fuming.

“Okay,” I said finally. “I’ll tell you how I feel. When you get on me about my weight I want to kick you in the head.”

I was shocked at the force of the words that came out of my mouth. Then I felt guilty for speaking this way to my mother. But she asked how I felt.

My mother was silent. She didn’t ask me about my feelings for a long time after that, but she also stopped bugging me about my weight.

My life was too entangled with my mother’s for comfort. An only child, I absorbed her like a sponge, losing a sense of where she left off and I began.

The irony, perhaps, inherent in the tensions and difficulties between us, was that we were both so much alike. Despite her increasing resignation, I wanted her to talk about her life, including her hopes and dreams that didn’t come true. She refused and in the face of her obstinacy, I became more insistent. Deep down, I felt my mother slipping away from me. My reaction to this was despair and, beyond despair, desperation. I wanted, needed, to know about the missing pieces of my mother’s life—the puzzle that created me. The catch was that my mother wanted the same thing from me and I, too, could not deliver.

Each of us had, what my mother called selective memory. We only remembered what we wanted to, and fought like hell to forget the rest.

In my teens and twenties I often reacted to my mother’s mixed messages with knee-jerk defensiveness, sometimes outrage. In my thirties, I found it easier to join her than to fight. Since my mother didn’t want to talk about her health during my visit, I turned to inquiring about my grandmother’s life.

“Didn’t Grandmom work in a shop?”

“A shop?” My mother looked at me like I was someone else’s daughter.

“Yeah,” I said, “I thought she worked in a store when she was a teenager.”

“No. That was a job. My mother was not educated. She didn’t qualify for a white-collar job—even to be a clerk in the store. She only went to the sixth grade. That put up a wall right there. Though, she probably learned more in six years than they do today in twelve. In those days, they focused on the basics, the three Rs they called them—reading, writing and arithmetic. None of the extras they have today, like the psychology of your navel.

“When your grandmother was a girl she worked in a candy factory,” my mother said, slowly and carefully.

I remembered that this was not the first time she had told me this.

“What did she want to do?”

My mother looked at me as if I were insane.

“No one asked her what she wanted to do,” she said. “She just went out and did it.”

She stared out the rectangular living room window into the late afternoon light. One foot rested on the ottoman’s rich autumn hues. She used to swing her foot up without thinking about it. Now, as she shifted in her chair, the pain that had invaded her body compressed her face. She squinted into the distance, beyond the tract houses across the street and the identical roofs behind them. She was searching the past, looking for something she lost there. She looked like a wistful child and at the same time an old, old woman, as old as she would ever be, looking back on a lifetime that spanned centuries.

Slowly, very slowly, she came back to the present. She stared at the ottoman. The far-away expression left her face. Lines of resignation weighed down the corners of her mouth. She stared at the ottoman for another moment and then spoke. “Your grandmother didn’t design that. They were all men, designers and artists, the ones who did the important work.”

My mother’s words registered on me with the sting of her own disappointments and thwarted dreams. Her abandoned portfolio was in the back of her closet, dusty and forgotten. The watercolors dried up into hard little squares long ago. The bristles on her paintbrushes had fallen off. The caps hardened onto the tubes of her oil paints. The pastels had lain there so long their colors rubbed off on each other, the orange laced with gray and blue, the pink with burnt sienna.

My mother was a woman who rejected the traditions that bound her mother’s life. Before I was born, she burned her Bibles in the backyard, disgusted with the hypocrisies, the contradictions, and, most of all, the misogyny inherent in the pages that curled into ash. My mother was a woman who tried to invent her own religion and failed. A Transcendental Meditation dropout (“I tried and tried to levitate—to bounce myself off the floor by flexing my butt muscles”), she joined the American Atheists for a few years only to leave in disillusionment (“They served coffee and doughnuts and passed the plate just like all the other idiots!”). She was a woman whose ambitions had been thwarted by circumstance, gender and class. She was a woman who absorbed her mother’s pain, made it her own, and passed it along to her daughter. When I tried to tell my mother that my grandmother’s life was worthwhile, important, I was trying to convince myself that my life, too, was important.

“Without Grandmom, the spinners, the weavers, the dyers, without the the patterns the designers thought up could never have been made into anything,” I said. But my words were weak, unconvincing. How could they be anything else, when I was not sure of myself?

My mother couldn’t give me what she herself never received. “Whatever I did was never good enough,” she said to me as we sat in the living room. “I never wore the right kind of hat, and even if I did I couldn’t keep it on my head.”

I laughed and went into the kitchen to fix myself a cup of chamomile tea. As I poured the water into the cup, I noticed a tear in the corner of the bag. A few tea leaves, crushed yellow flowers, seeped into the water and swirled around. I stared into the white porcelain tea-cup, wondering. What kind of life would I have if knowledge and wisdom were passed uninterrupted and uncensored, from my great-grandmothers down to my grandmother, mother and then to me? This world shimmered up at me for a fleeting moment. Then I saw the reflection of my mother’s face in mine. The lines of resignation, her disappointments and her fears stared up at me.

I shuddered, then skimmed the floating leaves away with a spoon and went back into the living room. Like my mother, I was a hopeless realist and at the same time I was deep in denial. I didn’t want to get the stray tea leaves on my tongue. Even if I could have divined the future by reading the tea leaf shapes of dark clouds and crosses, I would not have wanted to. I was wary of astrologists and fortune-tellers. It was more than a healthy dose of skepticism. It was superstition. I was afraid that if someone told me my future, I would have no choice other than to create that destiny for myself.

The only omens I could read were the memories of my past. When I was a child I brought home report cards saying I was an underachiever. In elementary school I came home with bit parts in plays in which my mother thought I should star. In junior high, my grades didn’t measure up to study the foreign languages in which she expected fluency.

When I reminded her of this, she denied it.

She accused me of wanting her to be better.

I, in turn, denied that I wanted my mother to be anyone except who she was.

Neither of us were as sure in our denials as we would have liked to be.

Only one thing was certain: whichever way we turned the mirror, the reflection came up wanting. My mother was more stubborn than me. Her mind was made up. Their lives, her mother’s and her own, were wasted, good for nothing but survival. No amount of arguing or cajoling could have changed that. But she nodded her head to appease me, and by so doing acknowledged that her life was linked with mine.

You can get copies of Tea Leaves, a memoir of mothers and daughters at your local library, your local bookstore or wherever books are sold online.

Read Full Post »